A global trend favouring large-scale interventions by Community Health Workers (CHWs) has paid huge and unexpected dividends in Chhattisgarh, where CHWs called mitanins have not only substantially improved infant mortality rates but are also meeting the goal of holistic development

.JPG) |

| Creating Bond of Friendship- Mitanins with Davapeti |

They've improved child survival rates in the state, furthered local women's participation in the community, and helped ensure people's right to food. What's more, Chhattisgarh's 60,000-strong volunteer Community Health Workers (CHWs), or mitanins ('friends' in the local language), have done all this in a relatively short period of time, armed with just a bag of basic drugs, a little training, loads of enthusiasm, and empathy.

A government-civil society partnership started in 2000, the mitanin programme is widely credited with bringing the rural Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in Chhattisgarh down from 85 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2002 (the second highest in the country) to 65 in 2005, much the same as the national rural IMR of 64.

Rewind to the beginning of the decade. In the context of high illiteracy and poverty, and with a third of the population being tribal, the 3,818 health sub-centres (staffed by one auxiliary nurse each) were unable to provide outreach services to the 18 million rural people dispersed over 54,000 habitations. Infants in the impoverished tribal- and scheduled caste-dominated region remained malnourished despite a network of anganwadis; primary health centres 'functioned' without doctors.

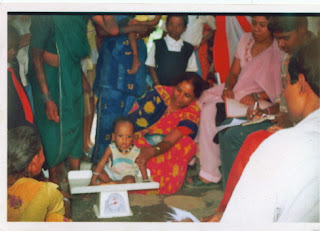

|

| Fighting against malnutrition- Weighting and followup of malnourished children |

There was an urgent need for someone to act as a link between the service and the beneficiaries, someone who could counsel the villagers and encourage them to seek improvements in service as a matter of right. Who best to do this but women from within the community itself?

In consultation with various civil society representatives, a government-funded network of 54,000 women community volunteers was formed through an MoU between the state government and civil society. The mitanin programme is run by an autonomous state health resource centre parallel to the health department.

The mitanin programme envisaged a synergy of health services at the community, outreach and facility levels as essential for its success. Mitanins would carry out family-level outreach activities such as essential care of newborns, nutritional counselling, and case management of illnesses that are common in childhood.

The role of these volunteers evolved over time into a set of activities that focused on child survival and essential care of newborns, and into another set of rights-based activities that enabled access to basic public services as fundamental entitlements to be secured through women's empowerment and community action.

A team of 3,000 motivated women were engaged as middle-level supervisors and trainers to address the issues of human resources and poor support from health personnel.

The Koriya region of Chhattisgarh may have been mineral-rich but its Gond and Kerwa tribal communities were dirt poor. Despite this, none of the government programmes, including the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) had reached them. Childhood infections were rampant, and infant mortality high.

Finally in 2003, the state government decided to appoint a mitanin in every village. The change thereafter is visible on the faces of children in Rokda village, where Rambai is a mitanin. Since being appointed, Rambai has treated hundreds of infections, tracked and counselled pregnant women on nutrition, and ensured that all infants were breastfed and immunised. "Earlier, women were starved for the first six days and the babies were fed cow or goat's milk with a cloth. Many children died as there was a lot of malnutrition. Now I tell women to breastfeed the children for six months, and then start on supplementary food. I tell the women to feed them five to six times, whatever they themselves eat. I also tell women to eat green leafy vegetables, depending on what is available. If there aren't any vegetables, I tell them grow them so that they don't have to buy them," she says.

Other mitanins in Koriya began sending complaints to the district collector about the poor state of anganwadis and primary health centres. When no action was taken, they approached the Supreme Court commissioners on the right to food. They wrote to the state government and action was immediate. About 10,000 complaints have so far been received against the public health centres alone, according to programme officials.

Now, even as the mitanins go about their work, the Dekh Rekh Samiti, a monitoring committee, visits anganwadis and schools every week to oversee their functioning. "We check whether teachers come or not, whether food is being served in the anganwadi and whether the rations are reaching pregnant women," says Gangabai, a member. In fact, they have already written to the administration that a new centre needs to be built near the school.

"Along with providing healthcare, the mitanins have focused on food programmes like the ICDS and midday meals scheme, and helped mobilise communities around them," says Samir Gar of the Adivasi Adhikar Samiti, Chhattisgarh. "Now there is a full house at the anganwadi, as children flock there for food, and Rambai helps the anganwadi worker with the cooking."

Malnutrition in Koriya has since dipped from 73% in 1999 to 66% in 2006.

|

| Mitanin gathered in a get together programme |

Today, there are mitanins in 60,092 of 72,000 hamlets in Chhattisgarh. "At least 45,000 of them are active in organising the community to access public health facilities and 6,000 were able to bring about some change in their community, to get doors opened for the villagers," says state coordinator Raman, a former activist at the Kerala Shastra Sahitya Parishad.

"Mitanins don't get salaries. The honour they get in society makes them come forward," says Raman. "In fact, 5,000 of them stood for panchayat elections and got elected," he adds. This is the biggest band of activists after China's barefoot doctors, proud officials claim.

"Much of the improvement in child survival rates in Chhattisgarh undoubtedly relates to better health-seeking behaviour and childcare practices. The initiation of breastfeeding during the first two hours after birth increased from 24% of live births to 71% of live births, and the use of oral rehydration salts in the management of diarrhoea in children younger than three years increased by 12% in the two weeks before the survey," says a review of the programme published in a recent issue of the British medical journal The Lancet. "Overall, the state has seen the number of underweight children fall from 61% to 52%. In addition to this, immunisation has increased from 22% to 49% in the 1-2 age-group."

By : Lisa Batiwalla, for InfoChange News and Features

By : Lisa Batiwalla, for InfoChange News and Features

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

JanMitram worked for Mitanins as implementing and Mentoring organisation till March 2011, in two blocks of Raigarh District. We were involved in programme, right from there selection (2003-04), and then sequential training that took many years. A network of over 830 Mitanins was created. This programme did so well that it was incorporated in Regular activities of Health Department, under National Rural Health Mission. However, organisation Still connected with Mitanins for strengthening and development of there social network.

Mitanin Sangthan, formed under exit policy of supporting organisation, now oversee issues and providing leadership. These blocks are now leading in district in major health indicators. The Sangthan is exemplary for strengthening of women based CBOs.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

JanMitram worked for Mitanins as implementing and Mentoring organisation till March 2011, in two blocks of Raigarh District. We were involved in programme, right from there selection (2003-04), and then sequential training that took many years. A network of over 830 Mitanins was created. This programme did so well that it was incorporated in Regular activities of Health Department, under National Rural Health Mission. However, organisation Still connected with Mitanins for strengthening and development of there social network.

Mitanin Sangthan, formed under exit policy of supporting organisation, now oversee issues and providing leadership. These blocks are now leading in district in major health indicators. The Sangthan is exemplary for strengthening of women based CBOs.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment